Burckhardt, who studied history in Berlin before returning to work as a journalist and university teacher in his native Basel, was very much part of the 19th-century discovery of Italy by the bourgeoisie. Italian cities were discovering art history as a commodity. The ruins, at that moment, were becoming less sleepy. In 1860 Burckhardt looked at Italy and saw the shock of the new, secreted in sleepy ruins. The fascination of reading his book is its vision of Italy as the birthplace of modern individualism, political calculation, science and scepticism. Northerners, from Thomas Mann in Death in Venice to Martin Amis picturing the gilded English young on holiday in a southern castle in The Pregnant Widow, have tended to imagine Italy as a languorous, sleepy, timeless and archaic place – the slow, hot unconscious of the European continent, drooping out into the Mediterranean like a surrealist appendage. It is, among other things, one of the most passionate homages ever paid by a northern European to southern Europe, and yet herein lies its strangeness. His book drips with love of Italy and Italians.

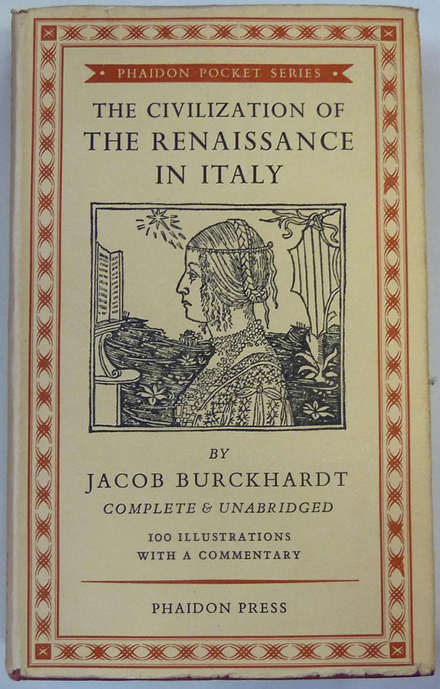

Darwin sailed to the Galápagos Burckhardt merely went to Italy. The study of the Renaissance can no more forget Burckhardt than biology can leave Darwin behind.īoth classics began in journeys. These two great 19th-century books are still at the living heart of their subjects. I believe this anniversary is as important as last year's of Darwin's On the Origin of Species. O ne hundred and fifty years ago the Swiss art lover and historian Jacob Burckhardt published his master work, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)